Angle Structures

The area in the anterior chamber where the cornea and iris join is known as the angle. This is comprised of several structures that make up the eye’s drainage system. The angle structures include: the outermost part of the angle, the front of the ciliary body, the trabecular meshwork, and the Canal of Schlemm.

Aqueous is formed in the ciliary body behind the iris. It flows through the pupillary space into the anterior chamber. From there, the fluid travels into the angle structures and drains from the eye.

As the aqueous fluid leaves the angle, it passes through a filter called the trabecular meshwork. After leaving the trabecular meshwork, the aqueous travels through a tiny channel in the sclera called the Canal of Schlemm. The aqueous flows into other tiny channels and eventually into the eye’s blood vessels.

The production and drainage of aqueous fluid determines the eye’s intraocular pressure (IOP).

Aqueous Humor

Aqueous Humor

The aqueous is the thin, watery fluid that fills the space between the cornea and the iris (anterior chamber). It is continually produced by the ciliary body, the part of the eye that lies just behind the iris. This fluid nourishes the cornea and the lens and gives the eye it’s shape.

Choroid

The choroid lies between the retina and sclera. It is composed of layers of blood vessels that nourish the back of the eye. The choroid connects with the ciliary body toward the front of the eye and is attached to edges of the optic nerve at the back of the eye.

The choroid lies between the retina and sclera. It is composed of layers of blood vessels that nourish the back of the eye. The choroid connects with the ciliary body toward the front of the eye and is attached to edges of the optic nerve at the back of the eye.

Ciliary

The ciliary body lies just behind the iris . Attached to the ciliary body are tiny  fiber “guy wires” called zonules.The crystalline lens is suspended inside the eye by the zonular fibers. Nourishment for the ciliary body comes from blood vessels which also supply the iris.

fiber “guy wires” called zonules.The crystalline lens is suspended inside the eye by the zonular fibers. Nourishment for the ciliary body comes from blood vessels which also supply the iris.

One function of the ciliary body is the production of aqueous, the clear fluid that fills the front of the eye. It also controls accommodation by changing the shape of the crystalline lens. When the ciliary body contracts, the zonules relax.

This allows the lens to thicken, increasing the eye’s ability to focus up close. When looking at a distant object, the ciliary body relaxes, causing the zonules to contract. The lens becomes thinner, adjusting the eye’s focus. With age, everyone develops a condition known as presbyopia. This occurs as the ciliary body muscle and lens gradually lose elasticity, causing difficulty reading.

Conjunctiva

Conjunctiva

The conjunctiva is the thin, transparent tissue that covers the outer surface of the eye. It begins at the outer edge of the cornea, covering the visible part of the sclera, and lining the inside of the eyelids. It is nourished by tiny blood vessels that are nearly invisible to the naked eye.

The conjunctiva also secretes oils and mucous that moisten and lubricate the eye.

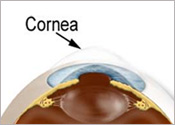

Cornea

The cornea is the transparent, dome-shaped window covering the front of the eye. It is a powerful refracting surface, providing 2/3 of the eye’s focusing power. Like the crystal on a watch, it gives us a clear window to look through. Because there are no blood vessels in the cornea, it is normally clear and has a shiny surface. The cornea is extremely sensitive – there are more nerve endings in the cornea than anywhere else in the body. The adult cornea is only about 1/2 millimeter thick and is comprised of 5 layers: epithelium, Bowman’s membrane, stroma, Descemet’s membrane and the endothelium.

The cornea is the transparent, dome-shaped window covering the front of the eye. It is a powerful refracting surface, providing 2/3 of the eye’s focusing power. Like the crystal on a watch, it gives us a clear window to look through. Because there are no blood vessels in the cornea, it is normally clear and has a shiny surface. The cornea is extremely sensitive – there are more nerve endings in the cornea than anywhere else in the body. The adult cornea is only about 1/2 millimeter thick and is comprised of 5 layers: epithelium, Bowman’s membrane, stroma, Descemet’s membrane and the endothelium.

The epithelium is layer of cells that cover the surface of the cornea. It is only about 5-6 cell layers thick and quickly regenerates when the cornea is injured. If the injury penetrates more deeply into the cornea, it may leave a scar. Scars leave opaque areas, causing the corneal to lose its clarity and luster.

Boman’s membrane lies just beneath the epithelium. Because this layer is very tough and difficult to penetrate, it protects the cornea from injury.

The stroma is the thickest layer and lies just beneath Bowman’s. It is composed of tiny collagen fibrils that run parallel to each other. This special formation of the collagen fibrils gives the cornea its clarity.

Descemet’s membrane lies between the stroma and the endothelium. The endothelium is just underneath Descemet’s and is only one cell layer thick. This layer pumps water from the cornea, keeping it clear. If damaged or disease, these cells will not regenerate.

Tiny vessels at the outermost edge of the cornea provide nourishment, along with the aqueous and tear film.

Extraocular Muscles

The six tiny muscles that surround the eye and control its movements are known as the extraocular muscles (EOMs). The primary function of the four rectus muscles is to control the eye’s movements from left to right and up and down. The two oblique muscles move the eye rotate the eyes inward and outward.

All six muscles work in unison to move the eye. As one contracts, the opposing muscle relaxes, creating smooth movements. In addition to the muscles of one eye working together in a coordinated effort, the muscles of both eyes work in unison so that the eyes are always aligned.

Eyelids

The eyelids protect the eyes from the environment, injury and light. They maintain a smooth corneal surface by spreading tears evenly over the eye. The lids are composed of an outer layer of skin, a middle layer made of muscle and tissue that gives them form, and an inner layer of moist conjunctival tissue.

Fovea

The fovea (arrow) is the center most part of the macula. This tiny area is responsible for our central, sharpest vision. A healthy fovea is key for reading, watching television, driving, and other activities that require the ability to see detail. Unlike the peripheral retina, it has no blood vessels. Instead, it has a very high concentration of cones (photoreceptors responsible for color vision), allowing us to appreciate color.

Iris

The colored part of the eye is called the iris. It controls light levels inside the eye similar to the aperture on a camera. The round opening in the center of the iris is called the pupil. The iris is embedded with tiny muscles that dilate (widen) and constrict (narrow) the pupil size.

The sphincter muscle lies around the very edge of the pupil. In bright light, the sphincter contracts, causing the pupil to constrict. The dilator muscle runs radially through the iris, like spokes on a wheel. This muscle dilates the eye in dim lighting.

The iris is flat and divides the front of the eye (anterior chamber) from the back of the eye (posterior chamber). Its color comes from microscopic pigment cells called melanin. The color, texture, and patterns of each person’s iris are as unique as a fingerprint.

Lens

The crystalline lens is located just behind the iris. Its purpose is to focus light onto the retina. The nucleus, the innermost part of the lens, is surrounded by softer material called the cortex. The lens is encased in a capsular-like bag and suspended within the eye by tiny “guy wires” called zonules.

In young people, the lens changes shape to adjust for close or distance vision. This is called accommodation. With age, the lens gradually hardens, diminishing the ability to accommodate.

Macula

The macula is located roughly in the center of the retina, temporal to the optic nerve. It is a small and highly sensitive part of the retina responsible for detailed central vision. The fovea is the very center of the macula. The macula allows us to appreciate detail and perform tasks that require central vision such reading.

Optic Nerve

The optic nerve transmits electrical impulses from the retina to the brain. It connects to the back of the eye near the macula. When examining the back of the eye, a portion of the optic nerve called the optic disc can be seen.

The pupil is the opening in the center of the iris. The size of the pupil determines the amount of light that enters the eye. The pupil size is controlled by the dilator and sphincter muscles of the iris. Doctors often evaluate the reaction of pupils to light to determine a person’s neurological function.

Pupil

The pupil is the opening in the center of the iris. The size of the pupil determines the amount of light that enters the eye. The pupil size is controlled by the dilator and sphincter muscles of the iris. Doctors often evaluate the reaction of pupils to light to determine a person’s neurological function.

Retina

The retina is a multi-layered sensory tissue that lines the back of the eye. It contains millions of photoreceptors that capture light rays and convert them into electrical impulses. These impulses travel along the optic nerve to the brain where they are turned into images.

There are two types of photoreceptors in the retina: rods and cones. The retina contains approximately 6 million cones.

The cones are contained in the macula, the portion of the retina responsible for central vision. They are most densely packed within the fovea, the very center portion of the macula. Cones function best in bright light and allow us to appreciate color.

There are approximately 125 million rods. They are spread throughout the peripheral retina and function best in dim lighting. The rods are responsible for peripheral and night vision. This photograph shows a normal retina with blood vessels that branch from the optic nerve, cascading toward the macula.

Sclera

The sclera is commonly known as “the white of the eye.” It is the tough, opaque tissue that serves as the eye’s protective outer coat. Six tiny muscles connect to it around the eye and control the eye’s movements. The optic nerve is attached to the sclera at the very back of the eye.

In children, the sclera is thinner and more translucent, allowing the underlying tissue to show through and giving it a bluish cast. As we age, the sclera tends to become more yellow.

Tear Film

Tears are formed by tiny glands that surround the eye. The tear film is comprised of three layers: oil, water, and mucous. The lower mucous layer serves as an anchor for the tear film and helps it adhere to the eye. The middle layer is comprised of water. The upper oil layer seals the tear film and prevents evaporation.

The tear film serves several purpose. It keeps the eye moist, creates a smooth surface for light to pass through the eye, nourishes the front of the eye, and provides protection from injury and infection.

Tear Production

The eye’s tears are composed of three layers: oil, water and mucous. The outermost oily layer is produced by the meibomian glands which line the edge of the eyelids.

The watery portion of the tear film is produced by the lacrimal gland. This gland lies underneath the outer orbital rim bone, just below the eyebrow. The mucous layer comes from microscopic goblet cells in the conjunctiva.

With each blink, the eyelids sweep across the eye, spreading the tear film evenly across the surface. The blinking motion of the eyelids forces the tears into tiny drains found at the inner corners of the upper and lower eyelids. These drains are called puncta (plural for punctum).

The tear film travels from the puncta into the upper and lower canaliculus, which empty into the lacrimal sac. The lacrimal sac drains into the nasolacrimal duct which connects to the nasal passage. This connection between the tear production system and the nose is the reason your nose runs when you cry. Some patients can actually taste eye drops as they drain from the nasal passage into the throat.

Vitreous Humor

Most of the eye’s interior is filled with vitreous. There are millions of fine fibers intertwined within the vitreous that are attached to the surface of the retina. As we age, the vitreous slowly shrinks, and these fine fibers pull on the retinal surface. Usually the fibers break, allowing the vitreous to separate and shrink from the retina. This is a vitreous detachment.